#FactCheck-Mosque fire in India? False, it's from Indonesia

Executive Summary:

A social media viral post claims to show a mosque being set on fire in India, contributing to growing communal tensions and misinformation. However, a detailed fact-check has revealed that the footage actually comes from Indonesia. The spread of such misleading content can dangerously escalate social unrest, making it crucial to rely on verified facts to prevent further division and harm.

Claim:

The viral video claims to show a mosque being set on fire in India, suggesting it is linked to communal violence.

Fact Check

The investigation revealed that the video was originally posted on 8th December 2024. A reverse image search allowed us to trace the source and confirm that the footage is not linked to any recent incidents. The original post, written in Indonesian, explained that the fire took place at the Central Market in Luwuk, Banggai, Indonesia, not in India.

Conclusion: The viral claim that a mosque was set on fire in India isn’t True. The video is actually from Indonesia and has been intentionally misrepresented to circulate false information. This event underscores the need to verify information before spreading it. Misinformation can spread quickly and cause harm. By taking the time to check facts and rely on credible sources, we can prevent false information from escalating and protect harmony in our communities.

- Claim: The video shows a mosque set on fire in India

- Claimed On: Social Media

- Fact Check: False and Misleading

Related Blogs

The recent Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act, 2025, that came into force in August, has been one of the most widely anticipated regulations in the digital entertainment industry. Among provisions such as promoting esports and licensing of online gaming, the legislation notably introduces a blanket ban on real-money gaming (RMG). The rationale behind this was to reduce its addictive effects, protect minors, and limit the circulation of black-money. However, in reality, the Act has spawned apprehension about the legislative process, regulatory redundancy, and unintended consequences that can shift users and revenue to offshore operators.

From Debate to Prohibition: How the Act was Passed

The Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act was passed as a central law, providing the earlier fragmented state laws on online betting and gambling with an overarching framework. Proponents argue that, among other provisions, some kind of unified national framework was needed to deal with the scale of online betting due to its detrimental impact on young users. The current Act is a direct transition to criminalisation rather than the swings of self-regulation and partial restrictions used during the previous decade of incremental experiments in regulation. Stakeholders in the industry believe that this type of sudden, blanket action creates uncertainty and erodes confidence in the system in the long run. Further, critics have pointed out that the Bill was passed without adequate Parliamentary deliberation. A question has been raised about whether procedural safeguards were upheld.

Prohibition of Online RMG

Within the Indian context, a distinction has long been drawn between games of skill and games of chance, with the latter, like a lottery or a casino, being severely prohibited under state laws, whereas the former, like rummy or fantasy sports, have generally been allowed after being recognized as skill-based by court authorities. The Online Gaming Act of 2025 abolishes this distinction on the internet, thus banning all RMG actions that include cash transactions, regardless of skill or chance. The act also criminalises the advertising, facilitation, and hosting of such sites, thereby penalizing offshore operators with an Indian customer focus, and subjecting their payment gateways, app stores, and advertisers under its jurisdiction to penalties.

The Problem of Overlap

One potential issue that the Act presents is its overlap with the existing laws. The IT Rules 2023 mandate intermediaries in the gaming sector to appoint compliance officers, submit monthly reports, and undergo due diligence. The new Act introduces a three-level classification of games, whereas the advisories of the Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) under the Consumer Protection Act treat online betting as an unfair trade practice.

This multiplicity of regulations builds a maze where different Ministries and state governments have overlapping jurisdiction. Policy experts caution that such an overlap can create enforcement challenges, punish players who act within the law, and leave offshore malefactors undetected.

Unintended Consequences: Driving Users Offshore

Outright prohibition will hardly ever remove demand; it will only push it out. Offshore sites have taken advantage of the situation as Indian operators like Dream11 shut down their money games after the ban. It has already been reported that there is aggressive advertising by foreign betting companies that are not registered in India, most of which have backend infrastructure that cannot be regulated by the Act (Storyboard18).

This diversion of users to unregulated markets has two main risks. First, Indian players are deprived of the consumer protection offered to them in local regulation, and their data can be sent to suspicious foreign organizations. Second, the government loses control over the money flow that can be transferred via informal channels or cryptocurrencies or other obscure systems. Industry analysts are alerting that such developments may only worsen the issue of black-money instead of solving it (IGamingBusiness).

Advertising, Age Gating, and Digital Rights

The Act has also strengthened advertisement regulations, aligning with advisories issued by the Advertising Standards Council of India, which prohibits the targeting of minors. However, critics believe that the application remains inadequately enforced, and children can with comparative ease access unregulated overseas applications. In the absence of complementary digital literacy programs and strong parental controls, these limitations can be effectively superficial instead of real.

Privacy advocates also warn that frequent prompts, vague messages, or invasive surveillance can weaken the digital rights of users instead of strengthening them. Overregulation has also been found to create banner blindness in global contexts where users ignore warnings without first clearly understanding them.

Enforcement Challenges

The Act puts a lot of responsibilities on many stakeholders, including the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB) and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Platforms like Google Play and Apple App Store are expected to verify government-approved lists of compliant gaming apps and remove non-compliant or banned ones, as directed by the MIB and the RBI. Although this pressure may motivate intermediaries to collaborate, it may also have a risk of overreach when it is applied unequally or in a political way.

According to the experts, the solution should be underpinned by technology itself. Artificial intelligence can be used to identify illegal advertisements, track illegal gaming in children, and trace payment streams. At the same time, the regulators should be able to issue final lists of either compliant or non-compliant applications to advise the consumers and intermediaries alike. Without such practical provisions, enforcement risks remaining patchy.

Online Gaming Rules

On 1 October 2025, the government issued a draft of the Online Gaming Rules in accordance with the Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Act. The regulations focus on the creation of the compliance frameworks, define the classification of the allowed gaming activities, and prescribe grievance-redressal mechanisms aiming to promote the protection of the players and procedural transparency. However, the draft does not revisit or soften the existing blanket prohibition on real-money gaming (RMG) and, hence, the questions about the effectiveness of enforcement and regulatory clarity remain open (Times of India, 2025).

Protecting Consumers Without Stifling Innovation

The ban highlights a larger conflict, i.e., the protection of the vulnerable users without stifling an industry that has traditionally contributed to innovation, jobs, and the collection of tax revenue. Online gaming has significantly added to the GST collections, and the sudden shakeup brings fiscal concerns (Reuters).

Several legal objections to the Act have already been brought, asking whether the Act is constitutional, especially as to whether the restrictions are proportional to the right to trade. The outcome of such cases will define the future trajectory of the digital economy of India (Reuters).

Way Forward

Instead of outright prohibition, a more balanced approach that incorporates regulation and consumer protection is suggested by the experts. Key measures could include:

- A definite difference between games of skill and games of chance, with proportionate regulation.

- Age confirmation and campaign against online illiteracy to protect the underage population.

- Enhanced advertising and payments compliance requirements and enforceable non-compliance penalty.

- Coordinated oversight among different ministries to prevent duplication and regulatory struggle.

- Leveraging AI and fintech to track illegal financial activities (black money flows) and developing innovation.

Conclusion

The Online Gaming Act 2025 addresses social issues, such as addiction, monetary risk, and child safety, that require governance interventions. However, the path it follows to this end, that of total prohibition, is more likely to spawn a new set of issues instead of providing solutions because it will send consumers to offshore sites, undermine consumer rights, and slow innovation.

For India, the real challenge is not whether to prohibit online money gaming but how to create a balanced, transparent, and enforceable framework that protects users while fostering a responsible gaming ecosystem. India can reduce the adverse consequences of online betting without keeping the industry in the shadows with better coordination, reasonable use of technology, and balanced protection.

References:

- India's Dream11, top gaming apps halt money-based games after ban

- India online gambling ban could drive punters to black market

- Offshore betting firms with backend ops in India not covered by online gaming law

- The Great Gamble: India’s Online Gaming Ban, The GST Battle, And What Lies Ahead.

- Game Over for Online Money Games? An Analysis of the Online Gaming Act 2025

- Government gambles heavily on prohibiting online money gaming

- Online gaming regulation: New rules to take effect from October 1; government stresses consultative approach with industry

Introduction

WhatsApp has become the new platform for scams, and the number of cases of WhatsApp scams is increasing daily. Just like that, a new WhatsApp scam has been started, and many WhatsApp users in India have reported receiving missed calls from unknown international numbers. Worse, one does not even have to answer the call to be scammed. A missed call is sufficient to be scammed.

Millions of populations switch from normal SMS to WhatsApp, usually, people used to get fake messages and marketing messages, but the trend of scamming has been evolving now. Most people get calls from different countries, and they are concerned about how these scammers got the numbers. WhatsApp works through VoIP networks, so no extra charges from any country exist. And about 500 million WhatsApp users are getting these scam calls, the calls are mainly on job-scams of promising part-time employment and opportunities. These types of job scam calls have been started reporting in 2023.

People reporting missed calls from countries like Ethiopia (+251), Malaysia (+60), Indonesia (+62), Vietnam (+84), etc.

The agenda of these calls are still unclear. Still, in some cases, the scammers ask for confidential information from WhatsApp users, like bank details, so the users must not reveal their personal information. Also, it is important to note that if you get any calls from a particular country, it necessarily does not mean it is from that country. Various agencies sell international numbers for WhatsApp calls.

Why has WhatsApp become a hub scam?

The generation has evolved and dumped the old SMS into WhatsApp. From school to college and offices, people use WhatsApp for their official work, as it is very easy and user-friendly, so people avoid safety measures. Generally, users need to understand the consequences of technology and use it with safeguards and awareness. Many people lose money and become victims of scams on WhatsApp as they share their confidential information. And the worse is that one does not even have to answer the call to be scammed. A missed call is sufficient to be scammed.

Before these international calls scam, the user received a call from the scam that they were from KBC, and the user won something. Then sought confidential information by the excuse that they would transfer the money to the user, and because of that user got scammed by the scammers. These scams have risen rapidly lately.

Safeguards users can use against these scam calls

WhatsApp responds to complaints regarding international calls to “block and report.”

If you have already received such calls, the best thing you can do is report and block them right away. As a result, the same number does not return to your phone, and numerous identical reports may persuade WhatsApp to delete the number entirely.

WhatsApp is also working on an update allowing users to block calls from unknown numbers on the service.

Users must modify their phone’s and app’s fundamental privacy settings to protect themselves from data breaches. The calls are directed toward app users who are actively using the app. However, by modifying the account’s appearance, a user can lessen the likelihood of being added to the scammers’ attack lists.

Limit Privacy

Begin by modifying WhatsApp’s ‘who can see’ settings. If your profile photo, last seen, and online status are visible to anybody, restrict them to persons on your contact list only. Change the About and Groups options as well.

Turn on two-factor authentication

Enabling two-factor authentication on WhatsApp adds more security to your data. In addition, the app also supports biometric protection in case of theft or loss.

Active Reporting

The users should report as soon as they see something odd or suspicious activity.

A typical question that users have is, ‘Where do the scammers acquire my phone number from?’

The answer is a little more complicated than we thought. Your data is retained on the company database from the time you sign up on a website or reveal your phone number at a store in order to take advantage of promotional offers and promotions. Due to a lack of technological infrastructure and legislation to protect personal data, a scammer can simply obtain your information.

According to Palo Alto research, India is the second most vulnerable country in the APAC region in terms of cyberattacks and data breaches. A data protection law is essential in the face of increasing calls and data breaches.

The Digital Personal Data Protection bill is set to be introduced in the parliament’s monsoon session. The bill has the potential to protect data, which will help to eliminate scams.

Conclusion

Several people had tweeted on tweeter about receiving fake calls on WhatsApp from international numbers more than once. WhatsApp encrypts calls and messages, making it difficult to track the person, and it appears that hackers are taking advantage of this to swindle customers. If you receive a WhatsApp call from any of the above ISD codes, we strongly advise you not to answer it and to block the number so the bad actors do not call you again. Report & block immediately that’s what WhatsApp has been responding to the complainants.

Executive Summary:

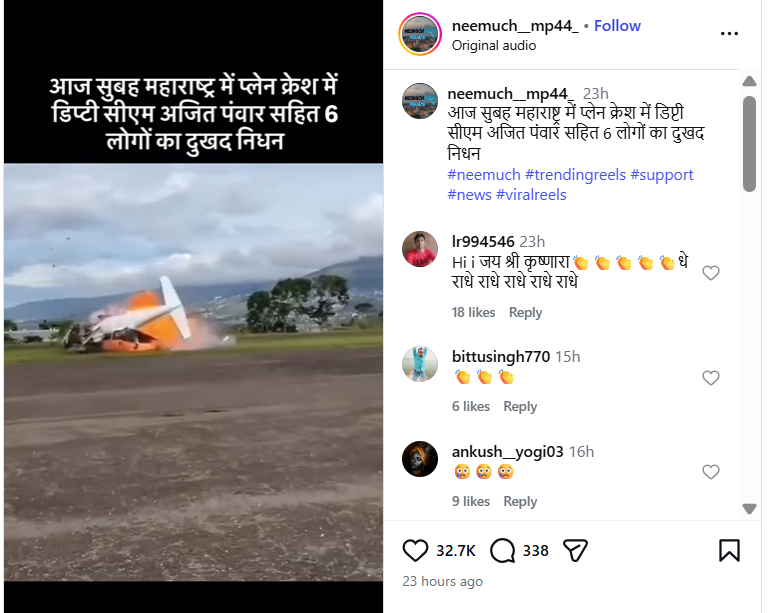

A video claiming to show the plane crash that allegedly killed Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar has been widely circulated on social media. The circulation began soon after reports emerged of a tragic aircraft accident in Baramati, Maharashtra, on January 28, 2026, in which Ajit Pawar and five others were reported to have died. The viral video shows a plane crashing to the ground moments after take-off. Social media users have claimed that the footage captures the exact incident in which Ajit Pawar was on board. However, an research by the CyberPeacehas found that this claim is false.

Claim:

An Instagram user shared the video on January 28, 2026, claiming that it showed the plane crash in Maharashtra in which Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar and others allegedly lost their lives. The caption accompanying the video read:“This morning, Deputy CM Ajit Pawar and six others tragically died in a plane crash in Maharashtra.”

Links to the post and its archived version are provided below.

Fact Check:

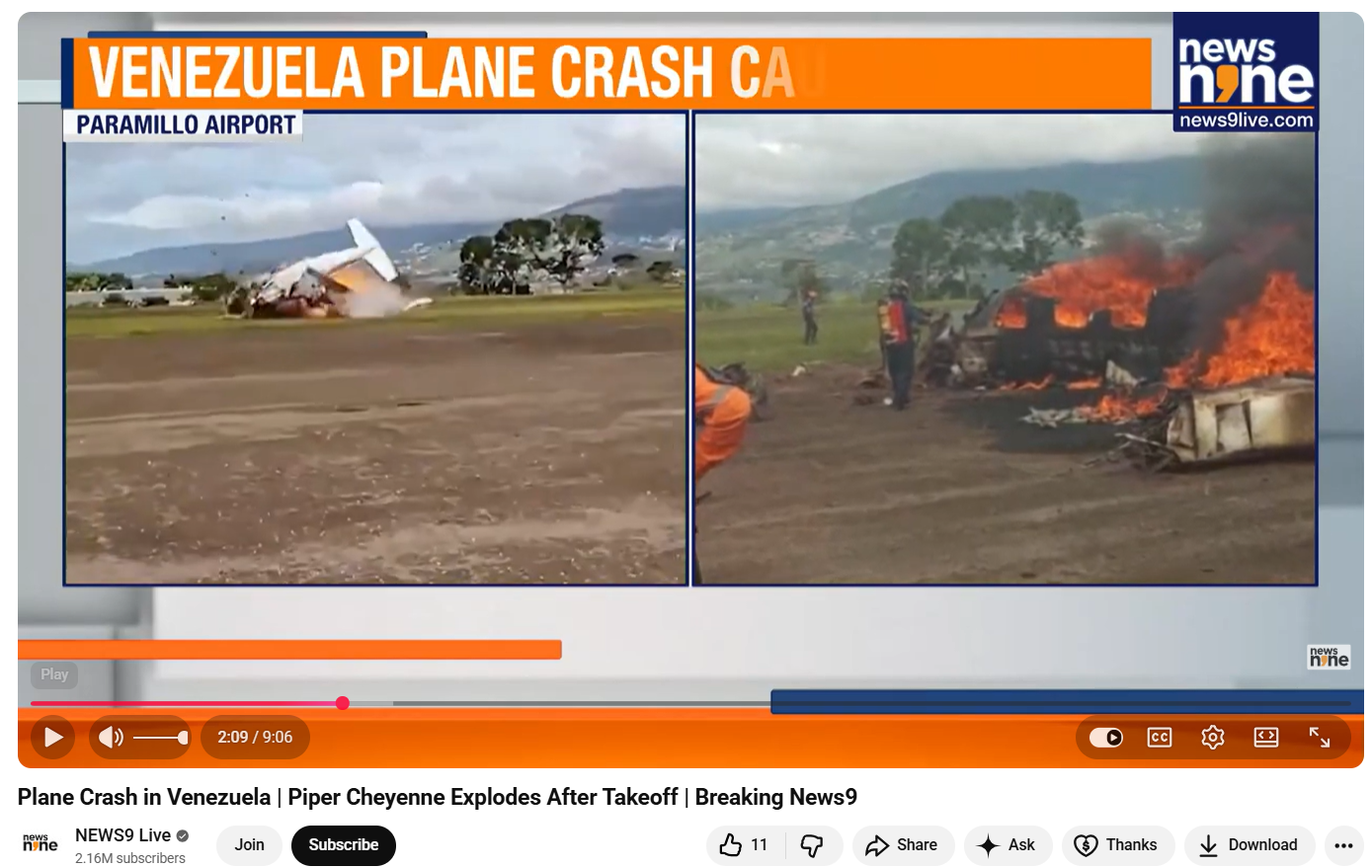

To verify the authenticity of the viral video, the CyberPeaceconducted a reverse image search of its keyframes. During this process, the same visuals were found in a video report uploaded on News9 Live’s official YouTube channel on October 23, 2025.

According to the report, the footage shows a plane crash in Venezuela, not India. The incident occurred shortly after a Piper Cheyenne aircraft took off from Paramillo Airport in Táchira, Venezuela. The aircraft crashed within seconds of take-off, killing both occupants on board. The deceased were identified as pilot José Bortone and co-pilot Juan Maldonado. Further confirmation came from a report published on October 22, 2025, by Latin American news outlet El Tiempo. The Spanish-language report also featured the same video visuals and stated that a small aircraft lost control and crashed on the runway at Paramillo Airport in Venezuela, resulting in the deaths of the pilot and co-pilot.

Conclusion

The CyberPeace’s research clearly establishes that the viral video being shared as footage of Ajit Pawar’s alleged plane crash in Baramati is misleading. The video actually shows a plane crash that occurred in Venezuela in October 2025 and has been falsely linked to a tragic claim in India.